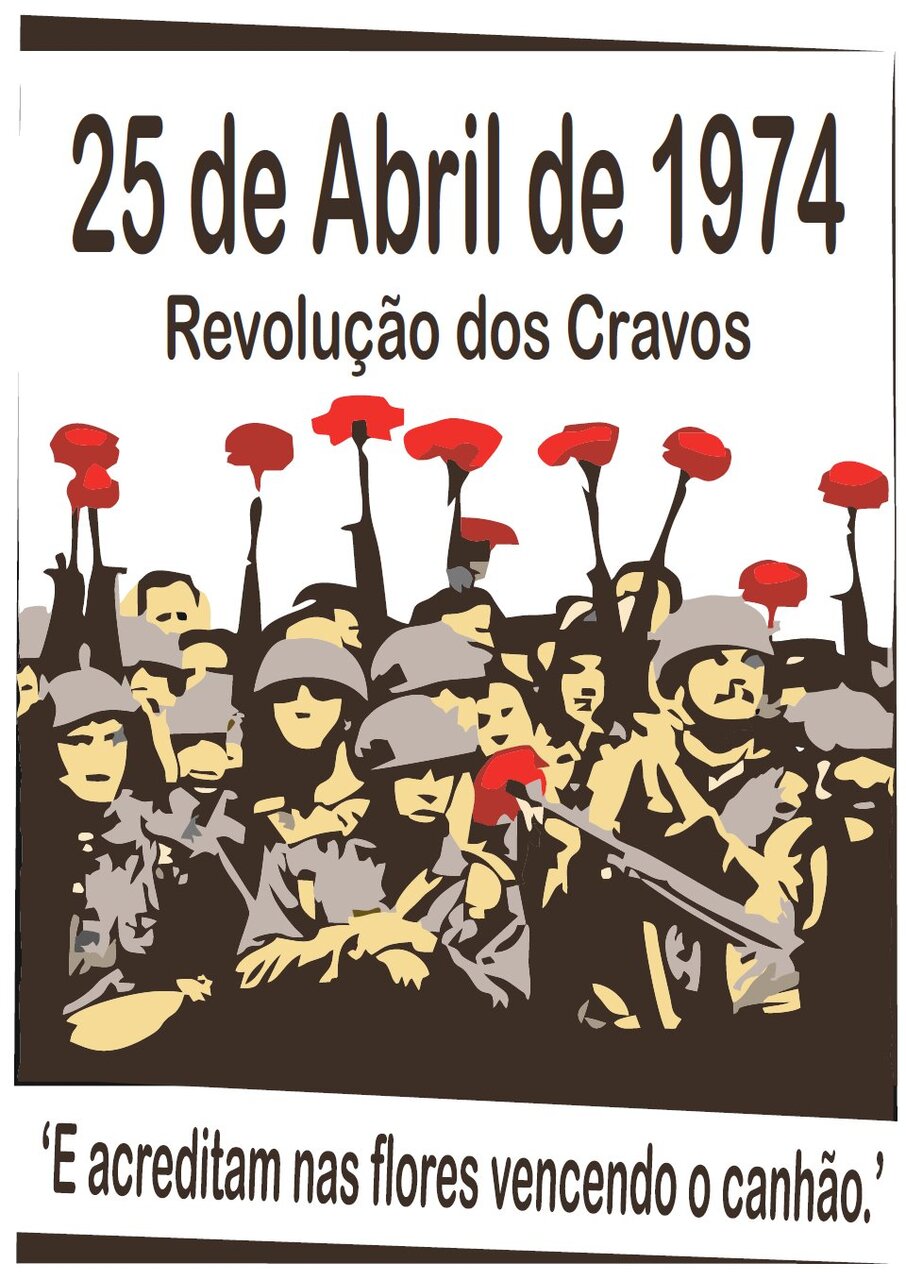

The Carnation Revolution; 25 April 1974

During one of Europe's lengthiest authoritarian regimes, Portugal's

governments were inspired by autocratic, authoritarian and fascist

ideologies. On 25th April 1974, in a coup led by left-leaning military

officers, the ‘New State’ was overthrown, leading to major social,

economic, territorial and demographic change.

YEARS ARE MEASURED IN EVENTS, NOT DAYS

Portugal

had become a republic following a military backed revolution on 5th

October 1910, in an uprising which abolished an ineffective and

unpopular monarchy, but from the beginning it created an unsettled

political climate. Universal suffrage had been promised, yet literacy

requirements reduced the male electorate to less than it had been under

the previous regime; the right to strike led to stoppages which

alienated the middle classes from protesting urban and rural workers;

and in the newly formed republic the president did not have the power to

dissolve Parliament, so the military became the accepted tool for this.

FORTY-FIVE

governments in sixteen years led to financial meltdown, and the First

World War exacerbated the problems. When, in 1926, the military

suspended the republican constitution, a great

number of people were not opposed to the action. Of course, with the

previous system in tatters, nobody was aware of what would follow for

close on the next four decades.

The leader for most of this

period was António de Oliveira Salazar, a prominent political economy

professor at the University of Coimbra, who entered the government as

finance minister. With Salazar at the helm there was financial stability

and budgetary surpluses which funded social programs, enabled

rearmament and developed infrastructure. However, the price paid for

these reforms was stifled politics and the means to finance wars in an

attempt to keep a grip on the country's colonies. Perhaps the greatest

cost for the Portuguese people though was the loss of personal freedom,

enforced by PIDE.

PIDE was the International and State Defense

Police; Portugal's security agency during the ‘Estado Novo’. Officers

had the power to detain and arrest anyone who was thought to be plotting

against the state, focusing on political and social issues such as

government opposition and revolutionary movements. Culture did not

escape the censorship either, books, the arts and music were all vetted.

There

was no freedom of speech, because on any street corner, at any dinner

party, in any shop a member of PIDE, or an informer, could be listening.

Saying the wrong thing to what seemed a friendly, sympathetic face

could leave you in prison, tortured or murdered.

FREEDOM ALSO HAS A PRICE

Of

course, the country's freedom from dictatorship also had a price, and

once again not only monetary. The aid given to Portugal in 1977 forced

the sale of 111 tons of the country's gold reserves and devalued the

currency, leading to greater competitiveness concerning exports, but

less spending power and higher inflation for her population.

Another

rescue package in 1986 led to higher taxes, spending cuts and a

devalued currency once again. On this occasion the drama played out as

the country continued to shake off the shackles of dictatorship by

installing the first civilian Head of State for sixty years.

Then,

in November 2010 when Stephen and I arrived in a Portugal, instead of

finally having emerged from the past the country was once more about to

have her sovereignty threatened —

OUR FIRST 25th ABRIL, 2011, MIRANDA DO CORVO

The ceremony on 25th of April 2011 marks the anniversary of freedom, but the feeling this year is one of fading hope.

Not

once, not twice, but three times Portugal is on the brink of receiving,

or having forced upon her, financial aid from outside her borders.

We

enter a room that is the usual setting for school meals but now has

rows of chairs arranged infront of an improvised stage. Behind this

platform is a large screen on which images and text is being displayed,

three men are sitting on chairs with their backs to these while a fourth

man is standing and speaking into a microphone. Two flags, one of

Portugal and another of Miranda do corvo fall in pleats against the

shafts of poles which are positioned at slight diagonals pointing away

from the four men; a beautiful arrangement of flowers sits on a table

within this tableau.

When we arrive there are no easily accessible

seats, so Stephen and I walk to the back of the room and stand there,

eventually leaning against a wall as the time passes. Our rudimentary

skills with the language enable us to garner the odd words but not the

meaning of the monologues being delivered. One gentleman finishes his

speech with an invitation for the President of the Câmara Municipal de

Miranda do Corvo to start hers, and an elegantly dressed woman takes

centre stage.

We recognise the face from posters we have seen

around the town, and we have certain ideas about the person behind those

images; our English friend Mary has a low opinion of the woman because

“She doesn't like English people”. Other opinions about her come from a

Portuguese neighbour who says that “She's like all politicians,

corrupt”. Yet all around us in the town we see investment that the

President had attracted to the area, because of this we tend to judge

the woman positively.

She begins to speak and her voice

commands attention. The audience is carried along on the wave of passion

with which she talks about Portugal, and in particular the small area

she represents. From slumped postures, daydreams and turning pages of

programmes, people are noticeably pulled back into the room. Backs

straighten and attention is focussed on the stage.

From the

little of the ceremony that Stephen and I comprehend it is enough for us

to understand that this year's talk of freedom is a particularly

poignant one for Portugal.

In my last blog I spoke about the

environment of fear that Stephen and I grew up in having lived in

London, but we always felt ‘free’. I felt that the government (of

whatever party) was generally trying to do the best for the people, and

even when I did not agree with the policies, I had little doubt that the

government was ‘on my side' and there to protect my freedom.

It was our parents and grandparents generations that lived with the threat of tyranny and the great

social changes brought by the two World Wars. They were the generations

that had to learn different ways of doing things and adjust to

different responsibilities. Our generation had our own social battles,

as I guess all generations do, but nothing that can rightly compare.

The

Portugal of today is not the Portugal that Stephen and I arrived in as

2010 died. Our first years in this country were influenced by the

financial restraints imposed by TROIKA, years in which we saw very

little investment and huge spending cuts. We knew people who left their

homes and country to find work elsewhere, those neighbours just a few

examples of what was occurring all throughout Portugal. Then, as the

country seemed to be recovering from this, COVID-19 arrived.

My

marido and I were once again shown the resilience and solidarity of the

Portuguese people, and as we saw with sadness and fear some of England's

measures in response to the pandemic, we became even prouder and

thankful to have found and settled in a new home.

After 13 years

we see a country that through sacrifices has become a more prosperous

place, but as of this time has not lost its soul, a country where money

is not, and hopefully never will be, master. Our Portugal is that which

is seen through the eyes of the younger generation, those aged 17 and

under who have no direct, and little indirect, experience of

dictatorship and the immediate political and social climate which

followed, similar to my generation in comparison with the two World

Wars.

This is a good thing in many ways, but it can make us

unappreciative of the freedoms and opportunities we have. We need to

remember the wrongs so as not to repeat them.

Much of this blog

is edited from the first book I wrote, a memoir about mine and Stephen's

first year in Portugal: Goodbyes & Bons Dias - R Silverthorne.

However, life in Portugal's ‘New State' dictatorship has been woven into

a small part of the story, in my novel Sempre; finding home.

O Revolução dos Cravos: 25 de abril

Durante

um dos regimes autoritários mais longos da Europa, os governos de

Portugal foram inspirados por ideologias autocráticas, autoritárias e

fascistas. No dia 25 de Abril de 1974, num golpe liderado por oficiais

militares de esquerda, o Estado Novo foi derrubado, conduzindo a grandes

mudanças sociais, económicas, territoriais e demográficas.

ANOS SÃO MEDIDOS EM EVENTOS, NÃO EM DIAS

Portugal

tornou-se uma república seguindo uma revolução apoiada pelos militares

no dia 5 de Outubro de 1910. A revolta aboliu uma monarquia ineficaz e

impopular, mas desde o início criou um clima político instável. O

sufrágio universal tinha sido prometido, mas os requisitos de

alfabetização reduziram o eleitorado masculino a menos do que no regime

anterior; o direito à greve levou a paralisações que alienaram as

classes médias dos protestos dos trabalhadores urbanos e rurais; e na

república recém-formada o presidente não tinha o poder de dissolver o

Parlamento, pelo que os militares tornaram-se a ferramenta aceite para

isso.

QUARENTA E CINCO governos em dezasseis anos resultaram num

colapso financeiro, e a Primeira Guerra Mundial exacerbou os problemas.

Quando, em 1926, os militares suspenderam a constituição republicana, um

grande número de pessoas não se opôs à acção. É claro que, com a

Constituição em farrapos, ninguém sabia o que ia seguir durante as

seguintes quatro décadas.

O líder durante a maior parte deste

período foi António de Oliveira Salazar, um proeminente professor de

política e economia na Universidade de Coimbra, que entrou o governo

como ministro das finanças. Com Salazar no lemo houve estabilidade

financeira e excedentes orçamentais que financiaram programas sociais,

permitiram o rearmamento e desenvolveram infra-estruturas. O preço que

as pessoas pagaram por estas reformas foi a política sufocada e os meios

para financiar as guerras , numa tentativa de manter o controlo sobre

as colónias do país. No entanto, talvez o maior custo para o povo

português tenha sido a perda da liberdade pessoal, imposta pela PIDE.

A

PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado) era a Agência de

segurança de Portugal durante o Estado Novo. Os oficiais tinham o poder

de deter e prender qualquer pessoa que se pensasse estar a conspirar

contra o Estado, concentrando-se em questões políticas e sociais, como a

oposição ao governo e os movimentos revolucionários. Mesmo a cultura

não escapou à censura, os livros, as artes e a música foram todos

examinados.

Não havia liberdade de expressão, porque em qualquer

esquina, em qualquer jantar, em qualquer loja podia estar a ouvir um

membro da PIDE, ou um informador. Dizer a coisa errada para quem parecia

uma cara amigável poderia deixá-lo na prisão, torturado ou assassinado.

A LIBERDADE TAMBÉM TEM PREÇO

É

claro que a libertação do país da ditadura também teve um preço, e mais

uma vez não apenas monetário. A ajuda Portugal recebia em 1977 obrigou à

venda de 111 toneladas das reservas de ouro do país e desvalorizou a

moeda resultando numa maior competitividade nas exportações, mas num

menor poder de compra e numa inflação mais elevada para a sua população.

Outro

pacote de resgate em 1986 resultou em impostos mais elevados, cortes de

gastos e uma moeda mais uma vez desvalorizada. Nesta ocasião, o drama

desenrolou-se à medida que o país continuava a libertar-se das algemas

da ditadura, instalando o primeiro Chefe de Estado civil em sessenta

anos.

Em Novembro de 2010, quando eu e o Stephen chegámos em

Portugal, em vez de finalmente ter emergido do passado o país estava

mais uma vez prestes a ter a sua soberania ameaçada —

O NOSSO PRIMEIRO ‘DIA 25 DE ABRIL’, 2011, MIRANDA DO CORVO

A cerimónia de 25 de Abril de 2011 marca o aniversário da liberdade, mas o sentimento este ano é de esperança esmagada.

Nem

uma, nem duas, mas três vezes Portugal está prestes a receber, ou a

ser-lhe forçado, ajuda financeira fora das suas fronteiras.

Entramos

numa sala que é o local habitual da merenda escolar, mas que agora tem

filas de cadeiras dispostas em frente a um palco improvisado. Atrás

desta plataforma há uma grande tela na qual imagens e textos são

mostrados, três homens estão sentados em cadeiras de costas para elas

enquanto um quarto homem está de pé e está a falar ao microfone. Duas

bandeira, uma de Portugal e outra de Miranda do corvo caem em pregas

contra as hastes dos mastros posicionados em ligeiras diagonais voltadas

para longe dos quatro homens; um lindo arranjo de flores fica em uma

mesa dentro deste quadro.

Quando chegamos, não há cadeiras de

fácil acesso, então Stephen e eu andamos até o fundo da sala e ficamos

lá, eventualmente encostados em uma parede conforme o tempo passa.

Nossas habilidades rudimentares com o idioma nos permitem compreender

algumas palavras, mas não o significado dos monólogos proferidos. Um

senhor terminou o seu discurso convidando o Presidente da Câmara

Municipal de Miranda do Corvo a iniciar o seu, e uma mulher

elegantemente vestida assume o centro do palco.

Reconhecemos a

cara dos cartazes que vimos pela vila e temos certas ideias sobre a

pessoa por trás dessas imagens; uma inglesa, Mary, tem uma opinião

negativa sobre a mulher porque “Ela não gosta de ingleses”. Outras

opiniões sobre ela vêm de um vizinho português que diz que “Ela é como

todos os políticos, corrupta”. No entanto, ao nosso redor na vila vemos

investimentos que o Presidente atraiu para a área, por isso tendemos a

julgar a mulher de forma positiva.

A Presidente começa a falar e

sua voz exige atenção. O público deixa-se levar pela onda de paixão com

que fala de Portugal e, em particular, do pequeno território que

representa. Desde posturas caídas, virando páginas de programas e

devaneios, as pessoas são visivelmente puxadas de volta para a sala. As

costas se endireitam e a atenção se concentra no palco.

Pelo

pouco da cerimónia que Stephen e eu compreendemos, basta-nos compreender

que o discurso deste ano sobre liberdade é particularmente comovente

para Portugal.

No meu último blog falei sobre o ambiente de medo

em que Stephen e eu crescemos por termos vivido em Londres, mas sempre

nos sentimos ‘livres’. Senti que o governo (de qualquer partido) estava

geralmente a tentar fazer o melhor para o povo, e mesmo quando não

concordava com as políticas, não tinha dúvidas de que o governo estava

“do meu lado” e lá para proteger a minha liberdade.

Foram as

gerações dos nossos pais e avós que viveram com a ameaça da tirania e

das grandes mudanças sociais trazidas pelas duas Guerras Mundiais. Foram

essas gerações que tiveram que aprender diferentes maneiras de fazer as

coisas e se ajustar a diferentes responsabilidades. Nossa geração teve

suas próprias batalhas sociais, como acho que todas as gerações têm, mas

nada que possa ser comparado com justiça.

O Portugal de hoje não

é o Portugal a que Stephen e eu chegámos quando 2010 se aproximava do

fim. Os nossos primeiros anos neste país foram influenciados pelas

restrições financeiras impostas pela TROIKA, anos em que assistimos a

muito pouco investimento e enormes cortes de despesas. Conhecíamos

pessoas que abandonaram as suas casas e o país para procurar trabalho

noutros locais, sendo estes vizinhos apenas alguns exemplos do que

estava a acontecer por todo o Portugal. Depois, quando o país parecia

estar a recuperar disto, chegou a COVID-19.

O meu marido e eu

vimos mais uma vez a resiliência e a solidariedade do povo português, e

ao vermos com tristeza e medo alguns reações à Pandemia na Inglaterra,

ficámos ainda mais orgulhosos e gratos por termos encontrado e sido

acolhidos num novo país.

Após 13 anos, vemos um país que através

de sacrifícios se tornou um lugar mais próspero, mas até agora não

perdeu a alma, um país onde o dinheiro não é, e esperamos que nunca

seja, mestre. O nosso Portugal é aquele que se vê através dos olhos das

gerações mais jovens, daqueles com 17 anos ou menos que não têm

experiência directa, e pouco indirecta, de ditadura e do clima político e

social que imediatamente se seguiu, semelhante à minha geração em

comparação com a duas Guerras Mundiais.

Isto é bom em muitos

aspectos, mas pode levar-nos a não apreciar as liberdades e

oportunidades que temos. Precisamos lembrar dos erros para não

repeti-los.

Ume grande parte deste blog é editado do meu

primeiro livro, umas memórias sobre o primeiro ano que eu e o Stephen

estivemos em Portugal: ‘Goodbyes & Bons Dias - R Silverthorne’. No

entanto, escrevo um pouco sobre a vida em Portugal durante o Estado Novo

no meu romance ‘Sempre; finding home'.

Post Views : 298